Venerable Ancestors: untangling the Chinese people's hybrid Pleistocene origins

More than 40,000 years of human evolution in East Asia

This piece extends on part 1: Genetic history with Chinese characteristics (also, accompanying podcast)

Sometime between 40,000 and 45,000 years ago, a few tribes of humans swept out of the Middle East and northern Africa, the inexorable waves of their descendants soon pulsing outward to every corner of the Old World. Those arrivals consistently overwhelmed the earlier human lineages already in residence, uprooting and supplanting them, conquest by conquest, ultimately leaping even to Australia and the New World, realms where no human had previously set foot. These prehistoric foragers originally from Africa percolating into the Middle East on their way to all habitable points beyond, were not the first modern human tribes to venture to the edges of Eurasia. We call these early Africans “anatomically modern humans” for their instantly recognizable flat faces, high foreheads and well-defined chins. This population, physically quite distinct from the far more robust Neanderthals of Europe and the Denisovans of Asia, emerged in Africa more than 200,000 years ago, but advanced parties seem to have migrated northward periodically, according to the whims of the climatic regime.

Anatomically modern humans with recent African origins had penetrated the fringes of Europe several times long before their ultimate conquest of the continent, always retreating in the face of Neanderthal expansion out of the north. A seesaw of dominance between Neanderthals and the southern African-derived humans had been in motion for millennia along the common frontier between the two populations, but this time was different. This time, a final demographic wave would crest, decisively clearing the Neanderthals from the evolutionary playing field, swamping them out genetically and obliterating them culturally. After hundreds of thousands of years of success in northern Eurasia, 40,000 years ago Neanderthals had disappeared across their ancient range, from the Atlantic Ocean to Mongolia. They simply vanished, leaving little more than minor genetic traces in the DNA of their vanquishers, plus an abundant legacy of scattered artifacts slowly decaying with time.

In the wake of the Neanderthal extinction, along Eurasia’s northern arc, south of the ice sheets, modern humans blazed a path far past their predecessors’ furthest frontier. Their more elaborated toolkit, including the bow and arrow, allowed modern humans to flourish further north than Neanderthals, deep in the tundra zone where massive mammoth herds roamed. Having leaped over the previous limits of Siberian hominin occupation by 45,000 years ago, modern humans rapidly multiplied across a frigid land of permafrost and glaciers. They pushed the charismatic native fauna like woolly mammoths and rhinoceroses to the brink, both populations eventually succumbing to the combined pressures of warmer post-Ice Age temperatures and relentless human predation. Meanwhile, far to the south and east, modern humans with the same technology vaulted nimbly over the Wallace Line that marks the southeastern ecological boundary of Asia as it fades into Oceania, eventually crossing over into the Australian continent 45,000 years ago. That arrival would trigger the extinction of dozens of species of exotic megafauna, from two-foot-long platypuses to 6,000-pound wombats.

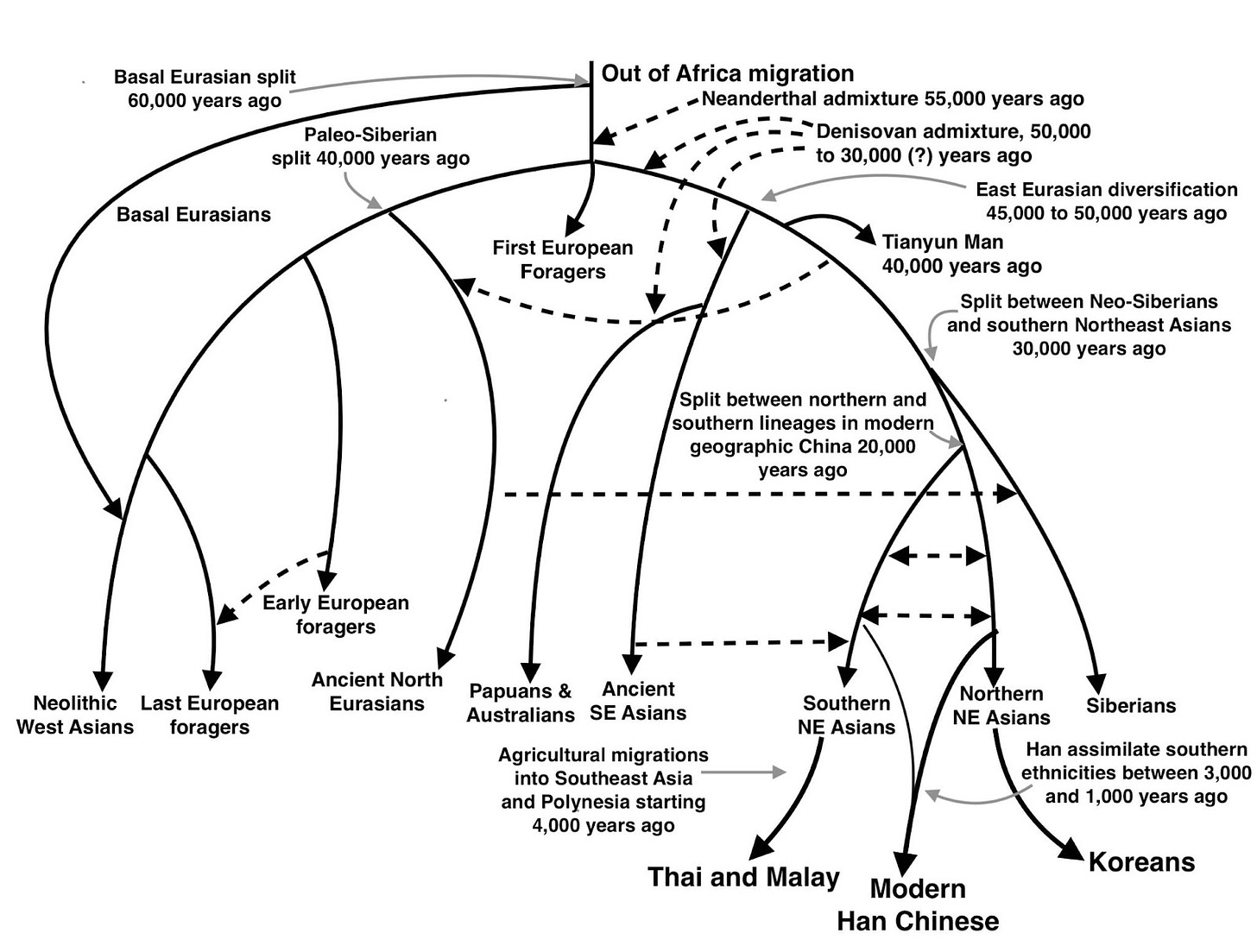

Amid all this migration, expansion and domination, by 41,000 years ago modern humans also arrived with finality in China. As in Europe, we find telltale signs of genetic and archaeological interactions between earlier waves of modern human populations descending from Africans and Eurasian hominins like Denisovans in China. But today’s populations descend almost exclusively from the last migration of modern humans that arrived 41,000 years ago. Archaeology and ancient DNA concur that all the human populations assuming control of territory amenable to foraging between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, were closely related, descended from an ancestral tribe or related tribes previously resident in the Middle East 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. Though the snapshot of ancient DNA captures many instances of matings between Neanderthals and modern humans, all contemporary populations outside of Africa (and today’s populations within Africa, as well, who carry smaller traces of Neanderthal DNA from subsequent Eurasian back-migration), from Australia to Patagonia to Scotland, bear the stamp of just a single mixing event with Neanderthals around 55,000 years ago. Comparison with Neanderthal genomes from Siberia and Europe indicates that the ancestral population modern humans mixed with was much closer to European Neanderthals. So the northern Middle East remains our top contender for the fateful event’s location, since this is both the way station from which African humans likely began to scatter in all directions, and, where there was a native population of Neanderthals that were genetically close to those in Europe.

But as our species began to disperse across Eurasia from a Middle Eastern starting point (beginning 50,000 years ago at the latest), modern humans defined by the out-of-Africa event also diversified and diverged, both genetically and in their physical appearance. When they crossed the Iranian plateau and descended into the tropical realm of southern Asia, they encountered those long-lost cousins of the Neanderthals, the Denisovans (whom genomics only rediscovered 12 years ago). Genomes from Chinese and East Asian populations generally show that the faint imprint of Denisovan ancestry (0.1 to 0.2% today) appeared in the region’s modern humans about 50,000 years ago. Denisovan heritage is lacking in all populations of western Eurasia and postdates the admixture with Neanderthals. During this time, western and eastern Eurasians parted, wending their way off on the two distinct routes that would result in their sharp genetic and cultural demarcation. The confluence of archaeological and genomic data makes plain that the roots of most of the “great human diasporas” L.L. Cavalli-Sforza (the 20th-century’s most eminent human population geneticist) identified and studied across his career took shape during this early period of expansion. Gracile African humans armed with an Upper Paleolithic toolkit put down stakes worldwide almost simultaneously, graduating from upstart parvenus to the last human species standing, Chris Stringer's evocative "Lone Survivors," just in the space between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago.

Advances in the study of ancient DNA mean that many locations where modern humans first settled now offer us ancient genomes to compare across different populations, times and places. Given the concentration of archaeology as a discipline in Europe and excellent preservation conditions for DNA in cooler weather, early European samples in particular abound. Surprisingly, the results indicate that the continent’s modern human pioneers were mostly evolutionary dead-ends. Comparing their genomes to contemporary humans, the earliest Europeans, and Siberians, are not closely related to any current population. They left no descendants, no kin. The “Cro-Magnon” man who conquered the Neanderthals was destined in his turn to fade into prehistory, forgotten, leaving no posterity.